with Margherita Vicario, Salvatore Caggiari, Elio D’Alessandro, Maurizio Stammati

Costumes: Barbara Caggiari

Lights: Antonio Palmiero

Sounds: Paolo Bellipanni

Scenography: Carlo De Meo

Assistant director: Francesca De Santis

Director: Maurizio Stammati

A Teatro Bertolt Brecht – Teatri Riuniti del Golfo’s production

with Margherita Vicario, Salvatore Caggiari, Elio D’Alessandro, Maurizio Stammati

Costumes: Barbara Caggiari

Lights: Antonio Palmiero

Sounds: Paolo Bellipanni

Scenography: Carlo De Meo

Assistant director: Francesca De Santis

Director: Maurizio Stammati

A Teatro Bertolt Brecht – Teatri Riuniti del Golfo’s production

TITLES

THE SHOW

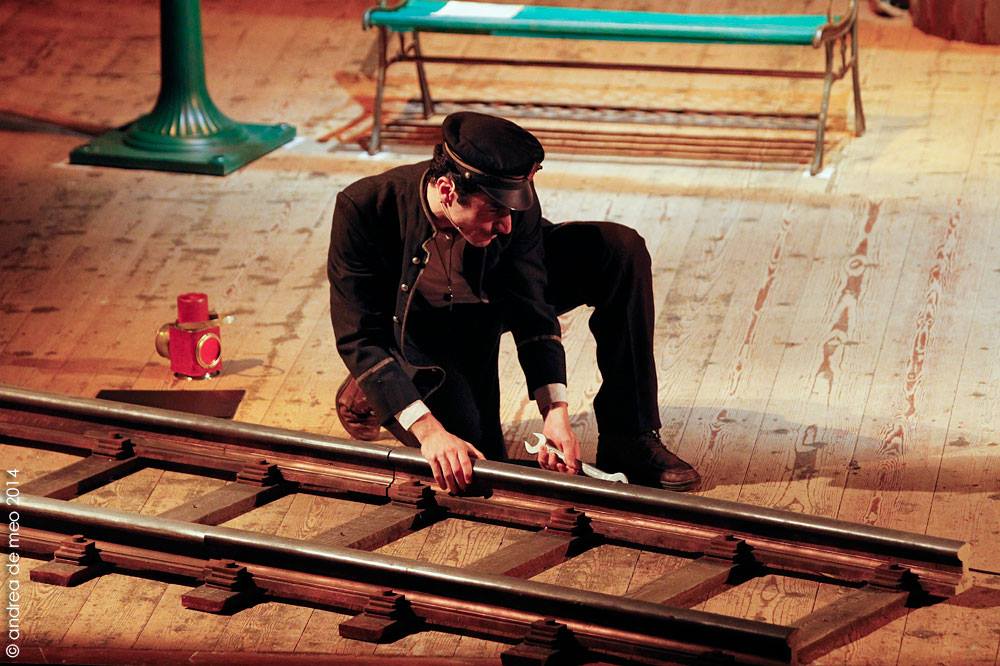

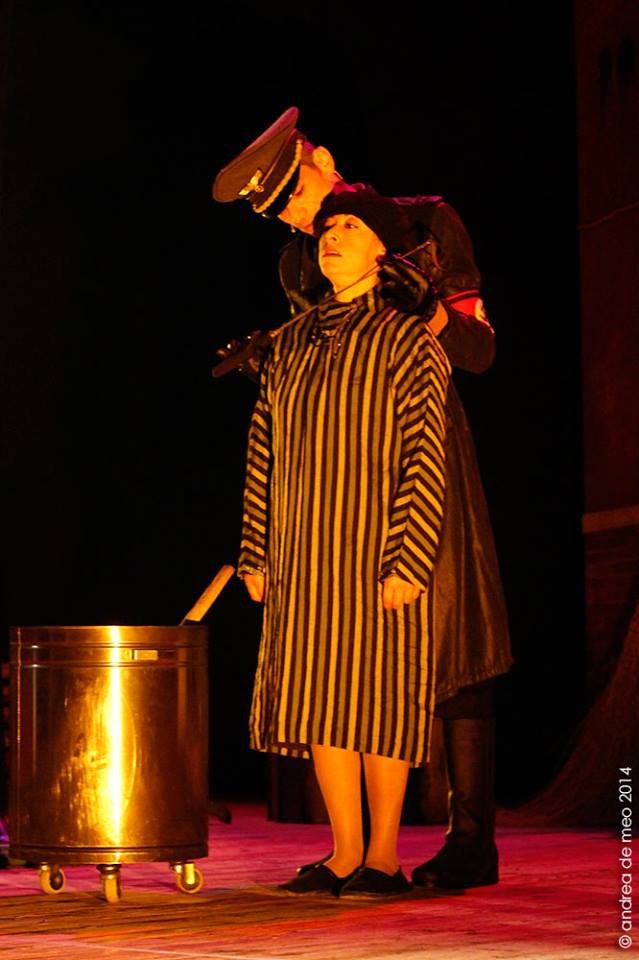

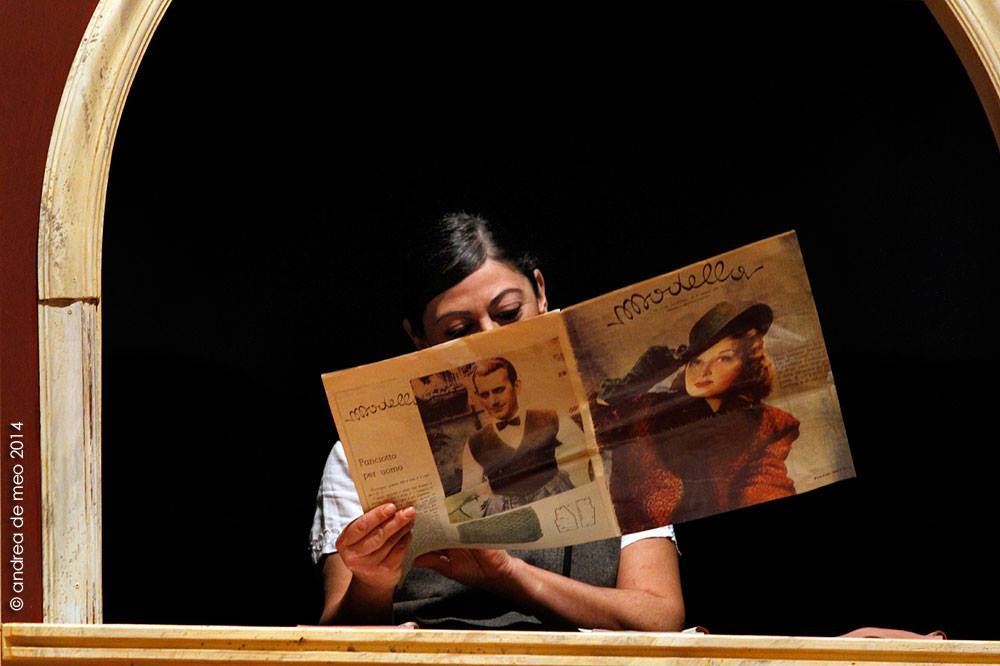

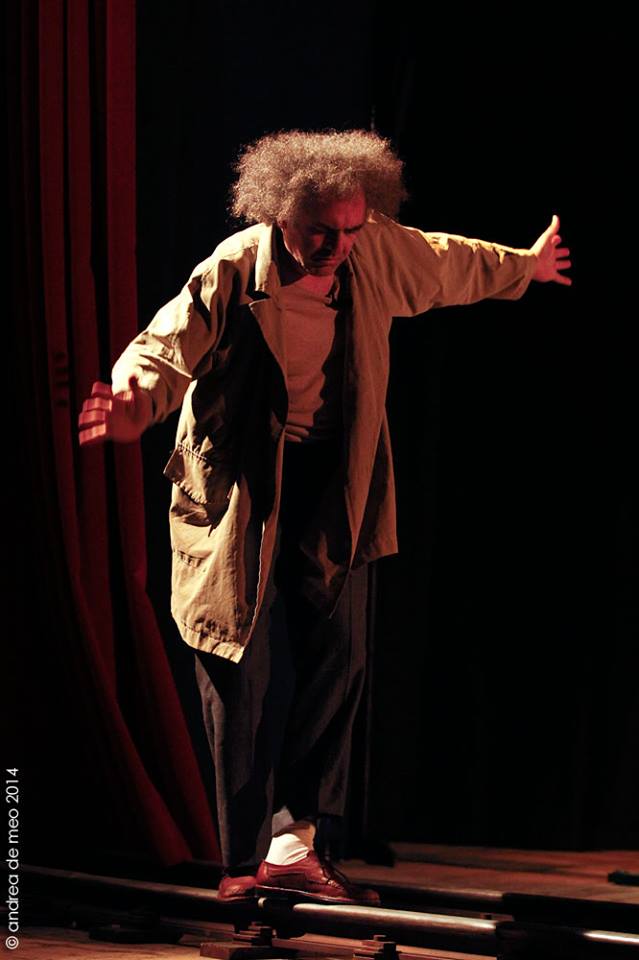

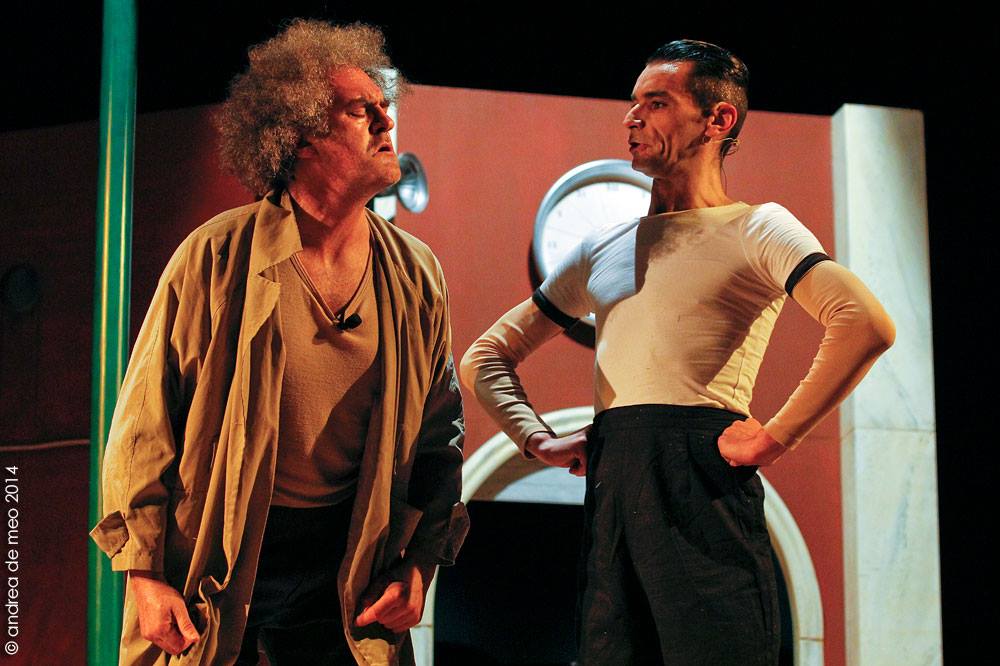

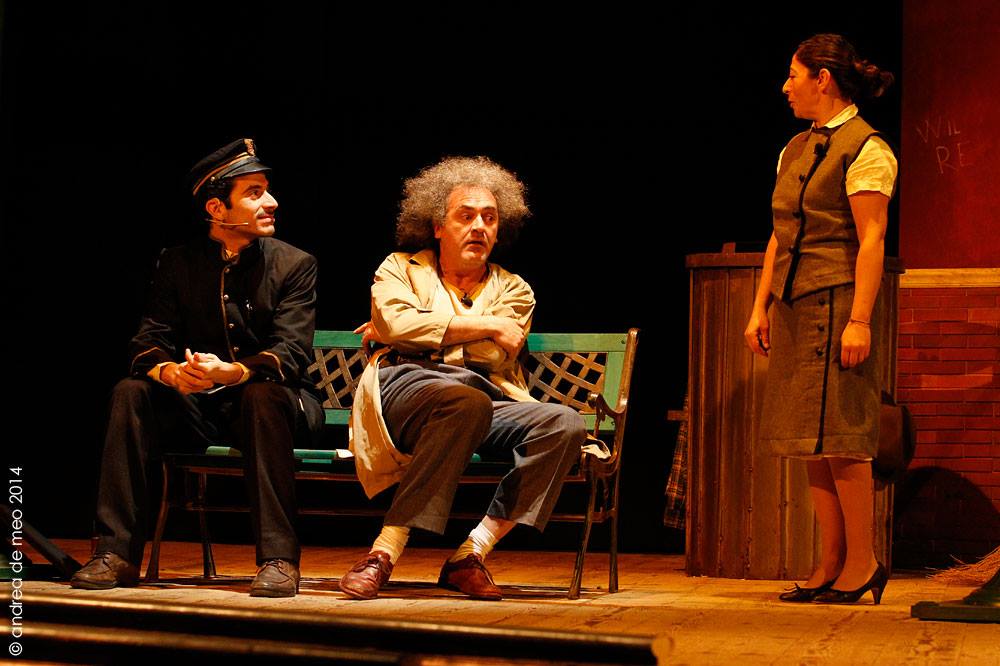

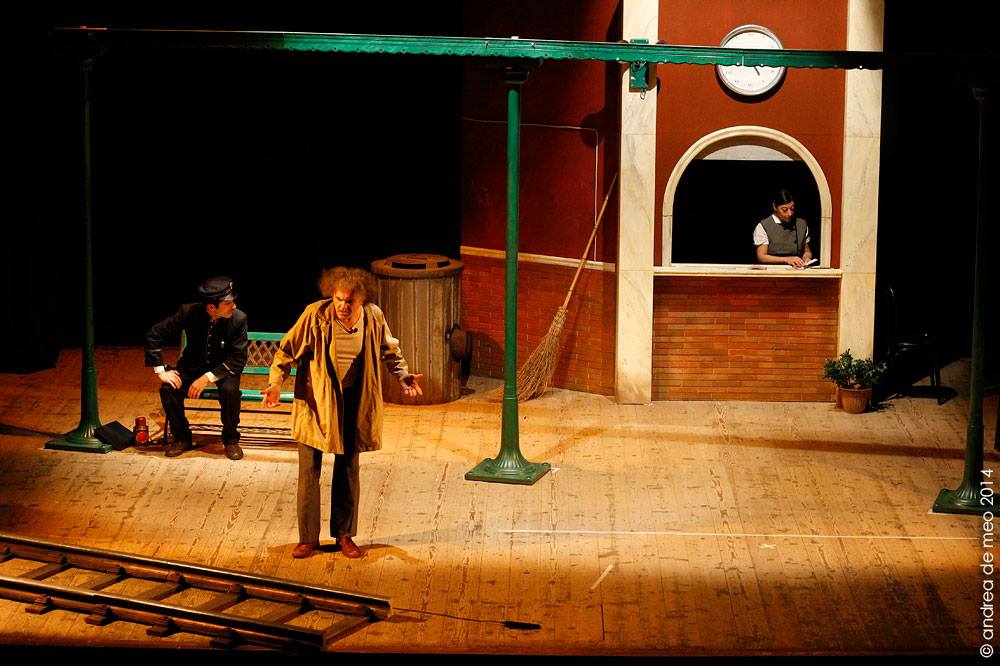

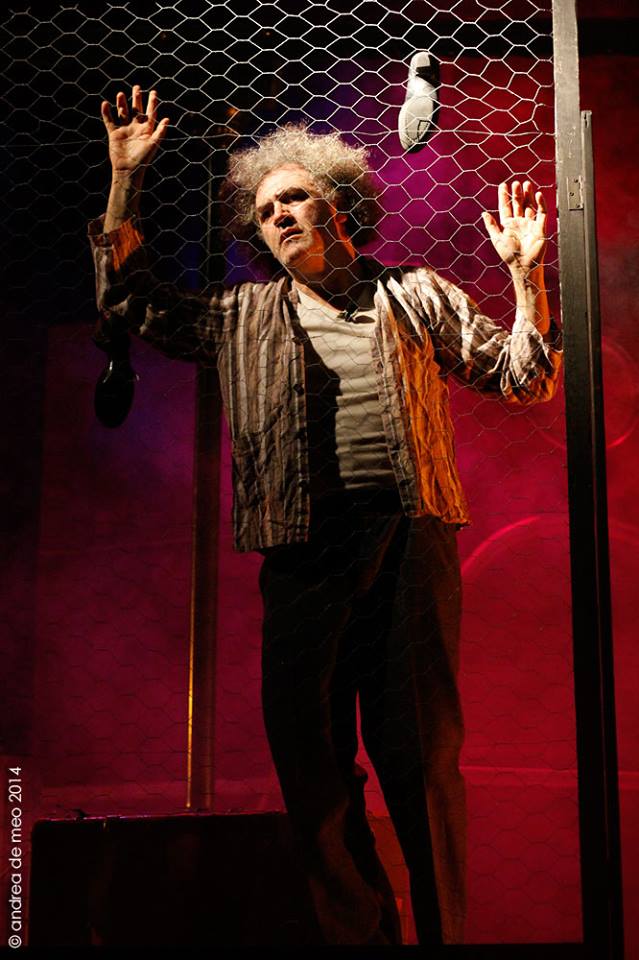

A small Italian railway station. A gentle stationmaster who has made of his job a second home. A cashier in love, but not too much, with a physical education teacher inspired by the ideology of fascism. And Angelo, who spends his day helping travelers carry their suitcases. Because Angelo can speak to suitcases. And they speak back to him. Or so he claims, when people ask him. In this ideal microcosm, ideal child of 1943, arrives David, a Jewish boy who runs away and hides from the eyes of all. Especially those of the audience. His arrival obliges everyone to make a decision, and to make a choice.

“On stage there is only Italy and only a clumsy attempt to tell the concentration and death camps in a language which is not ours, but that of suitcases , witnesses of horror no longer mute, but always difficult to interpret correctly.”

Alessandro Izzi

“The real problem was being able to balance on the razor blade without getting hurt. How to tell the greatest of the contemporary tragedies without falling into rhetoric , without locking it in the black of its brutality , without also trivializing or even worse ridiculing it ? Alessandro takes the bull by the horns: he chooses a train station as a place of representation, a symbol of the passage from life to death and he chooses a boy as a symbol of escape from death to life and he chooses the suitcases as story keepers , such as shells on which the good character of Angelo – the messenger – approaches his ear to listen to them.”

being able to balance on the razor blade without getting hurt. How to tell the greatest of the contemporary tragedies without falling into rhetoric , without locking it in the black of its brutality , without also trivializing or even worse ridiculing it ? Alessandro takes the bull by the horns: he chooses a train station as a place of representation, a symbol of the passage from life to death and he chooses a boy as a symbol of escape from death to life and he chooses the suitcases as story keepers , such as shells on which the good character of Angelo – the messenger – approaches his ear to listen to them.”

Maurizio Stammati

Crititcs

“The author works through the mechanism of identification, deep in the child audience, on an issue crucial to the psychological peculiarities of children spectators: the fear of being discovered , without terrorizing them . This point is the heart of the contact between the play and the Holocaust. There is no playing with petty sentimentalism. There is no work on the static contrast displayed in Life is beautiful, between life and death or good and evil. Here the author tries , in a fragment of representation , to make us sense the horror of having to hide. There is no need to dwell on the consequences. Because evil lurks there, in persecuting and being objects of hatred, before the concentration camp universe.”

Carlo Scognamiglio, recensione al testo in Esc@rgot

“The universality and harmony of the language of this play is a sweet lulling of souls wounded by the cruelty of man that, as in all the beautiful fairy tales, is at the end symbolically defeated thanks to the love of a child, the future and the hope of a better world.”

Monia Manzo (Close-up)

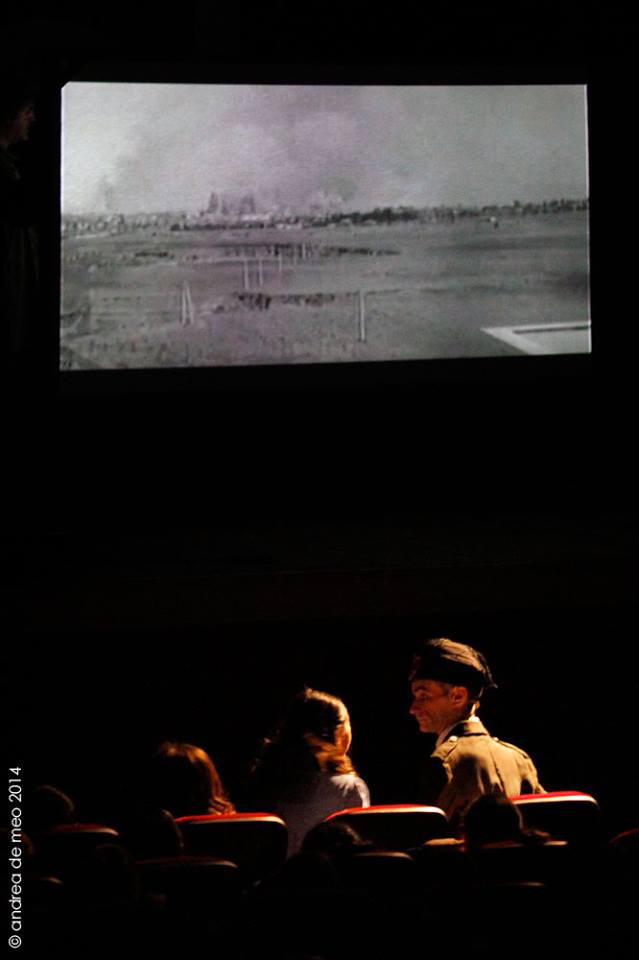

“The many historical references, literary and cinematographic , ranging from the irony of Yiddish stories during the brief interlude with puppets , to the texts of Primo Levi and films like Train of Life and Life is Beautiful (Benigni also inspired the name of the fool fascist Roberto ) are internalized within a short story that touches the moral purity of Gianni Rodari ‘s narrative , especially in the work of Angelo, a sort of Candide, an adult still in contact with his childhood and therefore able to understand the ” valigiese ,” the language of the suitcases that tell ” the story of many and of no one.”

Fabiana Proietti (Sentieri Selvaggi)

The show – recalling a consolidated topos such as the train – succeeds in its teaching , because it communicates complex messages in simple words and with strong images , insisting much on the relationship between the ideas and the words themselves.

Martina Micillo (Forumnews)

A text written for the theater that seems to fit perfectly to be read as a simple tale or as historical re- enactment but in simple language and at the same time direct and almost poetic , that does not hide – but rather emphasizes the absurd, still unexplainable atrocities of those years.

Roberto Zadik (Mosaico)

It’s not a good time for Jewish kids in Italy, and between newsreels that manipulate reality and news of Rome affected by Allied bombings, on stage we find the aforementioned railroad track, broken street lights , a bench , which take us back to “Man with the flower in the mouth” by Pirandello , the station office with Alessia’s booth, and a clock, a simulacrum of a sick time winding idly on . The lights are dim, always threatened by the shadow and become witness to the strategy of Michele and Angelo to save the little David.

Giammario Di Risio (Close-up)

The text of the play is published by deComporre editions .

A small Italian railway station. A gentle stationmaster who has made of his job a second home. A cashier in love, but not too much, with a physical education teacher inspired by the ideology of fascism. And Angelo, who spends his day helping travelers carry their suitcases. Because Angelo can speak to suitcases. And they speak back to him. Or so he claims, when people ask him. In this ideal microcosm, ideal child of 1943, arrives David, a Jewish boy who runs away and hides from the eyes of all. Especially those of the audience. His arrival obliges everyone to make a decision, and to make a choice.

“On stage there is only Italy and only a clumsy attempt to tell the concentration and death camps in a language which is not ours, but that of suitcases , witnesses of horror no longer mute, but always difficult to interpret correctly.”

Alessandro Izzi

“The real problem was being able to balance on the razor blade without getting hurt. How to tell the greatest of the contemporary tragedies without falling into rhetoric , without locking it in the black of its brutality , without also trivializing or even worse ridiculing it ? Alessandro takes the bull by the horns: he chooses a train station as a place of representation, a symbol of the passage from life to death and he chooses a boy as a symbol of escape from death to life and he chooses the suitcases as story keepers , such as shells on which the good character of Angelo – the messenger – approaches his ear to listen to them.”

Maurizio Stammati

Crititcs

“The author works through the mechanism of identification, deep in the child audience, on an issue crucial to the psychological peculiarities of children spectators: the fear of being discovered , without terrorizing them . This point is the heart of the contact between the play and the Holocaust. There is no playing with petty sentimentalism. There is no work on the static contrast displayed in Life is beautiful, between life and death or good and evil. Here the author tries , in a fragment of representation , to make us sense the horror of having to hide. There is no need to dwell on the consequences. Because evil lurks there, in persecuting and being objects of hatred, before the concentration camp universe.”

Carlo Scognamiglio, recensione al testo in Esc@rgot

“The universality and harmony of the language of this play is a sweet lulling of souls wounded by the cruelty of man that, as in all the beautiful fairy tales, is at the end symbolically defeated thanks to the love of a child, the future and the hope of a better world.”

Monia Manzo (Close-up)

“The many historical references, literary and cinematographic , ranging from the irony of Yiddish stories during the brief interlude with puppets , to the texts of Primo Levi and films like Train of Life and Life is Beautiful (Benigni also inspired the name of the fool fascist Roberto ) are internalized within a short story that touches the moral purity of Gianni Rodari ‘s narrative , especially in the work of Angelo, a sort of Candide, an adult still in contact with his childhood and therefore able to understand the ” valigiese ,” the language of the suitcases that tell ” the story of many and of no one.”

Fabiana Proietti (Sentieri Selvaggi)

The show – recalling a consolidated topos such as the train – succeeds in its teaching , because it communicates complex messages in simple words and with strong images , insisting much on the relationship between the ideas and the words themselves.

Martina Micillo (Forumnews)

A text written for the theater that seems to fit perfectly to be read as a simple tale or as historical re- enactment but in simple language and at the same time direct and almost poetic , that does not hide – but rather emphasizes the absurd, still unexplainable atrocities of those years.

Roberto Zadik (Mosaico)

It’s not a good time for Jewish kids in Italy, and between newsreels that manipulate reality and news of Rome affected by Allied bombings, on stage we find the aforementioned railroad track, broken street lights , a bench , which take us back to “Man with the flower in the mouth” by Pirandello , the station office with Alessia’s booth, and a clock, a simulacrum of a sick time winding idly on . The lights are dim, always threatened by the shadow and become witness to the strategy of Michele and Angelo to save the little David.

Giammario Di Risio (Close-up)

The text of the play is published by deComporre editions .